By Andy Winfield

The daffodil is symbolic to many of us; an innocent sign that winter and spring are side by side before walking away from each other taking the past and the future with them. The nodding yellow flowers of Narcissus can be bathed in sunshine or covered in snow, or, as I write this, blown horizontal by storm Eunice. It will weather all of this, experiencing everything that this time of year throws at it until it fades while other flowers form. Playing the role of seasonal buffer to perfection, the Narcissus must be able to withstand hungry bulb grubbers as well as the weather; it has become the icon it is through its attractiveness and its defences.

There’s a lot going on with the name of this plant; firstly, the common name ‘daffodil’ has origins in the name ‘asphodel’, a plant that is steeped in its own Greek mythology and a flower that the daffodil was compared to. Somewhere along to line the letter D was added, maybe someone had a cold when they were saying it, or hayfever… ‘dasphodel’ … anyway, added it was and daffodil was named.

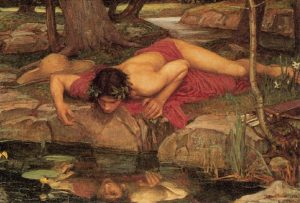

The Latin name Narcissus has a number of meanings. It is derived from the Greek word for intoxicated or numbness; this is a reference to the toxicity of the plant, every part is poisonous which is why squirrels leave them alone. If you put daffodils in a vase with other flowers, their sap will poison the water and you’ll see the innocent looking daffodil surrounded by the dead blooms of its vase neighbours. Fittingly, in Greek mythology, Narcissus was the handsome hunter who happened to see his reflection in a pool and couldn’t look away, he stayed by the water, head nodded over, looking at himself and nothing else, hence narcissist. In time, he melts away and all that is left is a Narcissus flower, its head nodding over the pool admiring itself, disallowing any floral friends; the toxins released from the bulb restrict growth of other plants around them.

In the wild the plant grows in Mediterranean regions through to the Iberian peninsula, anything in the UK here is a naturalised introduction. One species in particular N.pseudonarcissus is an ancient introduction but considered here a wild daffodil; also known as the lent lily. It is much smaller than garden centre varieties and can be found throughout the British Isles and particularly here on the West side. In Wales a sub-species, the Tenby daffodil (N.pseudonarcissus ssp.obvallaris), grows wild throughout the country and is the much loved national flower growing in drifts through woods and meadows.

Today there are over 13,000 species of daffodil divided into 13 descriptive divisions, from trumpet to triandus to tazetta, there is a place for all cultivars. Narcissus himself would be pleased with the attention that is heaped on this flower, and it is a welcome sight at a time when everyone needs to see signs of the warming soil and lengthening days. Nodding in its self-absorbed love of itself, toxic sap running through the stem, but brightening our world through all the weather that February and March can throw at it.

Fascinating – love the idea it’s nodding because it’s so pleased with itself!

I always understood the story was they were hanging their heads in sorrow because of the demise of St David hence them being the flower of Wales. As a young person I rarely saw daffs out before mid March so could never work that one out as St David’s day is 1st March. Of course now you can get daffs with a flowering period from December onwards and plant them for succession of blooms for several months.

Thank you Frances, we didn’t know about the hanging heads in sorrow story; it’s a plant that inspires stories and poetry wherever it goes!

What a wonderful and lyrical history of the daffodil. I like that the daff in the second image mirrors the posture of Narcissus gazing into the pond. I’m sure that I’ll now think of that every time I encounter daffodils…